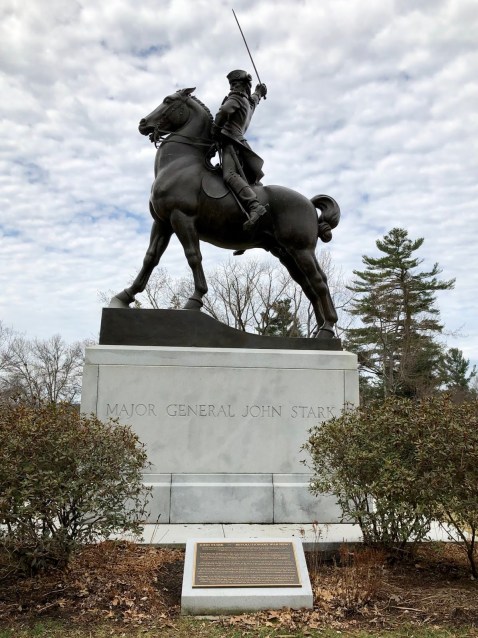

If New Hampshire has a favorite son, it’s John Stark. The State Motto is a truncated quote from Stark, “Live Free or Die” and of course the people of New Hampshire have a certain Stark independent streak that lives on to this day. As a transplant from Massachusetts who lives 7 miles from where Stark was born, I’ve come to appreciate the New Hampshire way of thinking more each year. This is my 25th year in the Granite State and it’s high time I focus on New Hampshire’s Revolutionary War hero.

In each phase of John Starks adult life he had extraordinary moments that would on their own be the highlight of someone else’s story. As a 24 year-old young man he was captured by the Abenaki while hunting near the Baker River/Mount Moosilauke area. In captivity he was forced to run the gauntlet but grabbed the stick from the first warrior in the line and attacked him instead! This endeared him to the Abenaki and they adopted him into the tribe. He was eventually ransomed back to freedom but this time with the Abenaki would remain a part of him.

Five years later, with the French and Indian War making New Hampshire a war zone, Stark joined Robert Rogers as a Second Lieutenant and later Captain in Roger’s Rangers. He participated in many of the legendary battles of the Rangers, including Battle on Snowshoes and other skirmishes around Lake George, New York. Stark learned a lot from the tactics of Rogers, who in turn had adopted the tactics from the Native American warriors they were fighting against. This would prove handy in the war to come.

One event that Stark chose to sit out was the raid on St. Francis, an Abenaki village just over the present-day border of Canada. Stark opting out was a sign of respect for those who he lived with five years before during his captivity. It’s a great indicator of his character.

After the war, Stark returned to his home in Nutfield (Londonderry) to work his farm. Stark was married to Molly Page Stark, a legend in her own right, and had 11 children. The Starks were clearly productive on the home front when they weren’t fighting wars. Molly was a champion for smallpox vaccination, which involved deliberately infecting yourself with a small bit of smallpox, which, if it didn’t kill you, would make you immune to a worse case of it. Smallpox was a major threat to the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

During the Revolutionary War, John Stark became a legend. He was one of the first to answer the call to arms, and fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill, where his experience in the Rangers paid dividends. Stark’s saw immediately what the vulnerabilities were on the northern flank in the defense of Breeds Hill and built a breastwork from old stone walls to defend the Americans from a possible beach landing on the Mystic River. This proved to be salient as that’s exactly what the British did.

In a brilliantly orchestrated defense, the first line of New Hampshire militia fired on the attacking British and ducked down to reload. The British kept advancing with fixed bayonets but were mowed down by a second line. And then a third line mowed down the advancing British. By then the first line had reloaded and mowed down the still advancing British and they finally retreated, abandoning the flanking strategy for a full frontal assault elsewhere.

Stark would later serve George Washington at Princeton and Trenton, but unlike Benedict Arnold, he chose to tell the Continental Congress to take a hike when they passed him over for politically motivated promotions to General. He returned to New Hampshire but left the door open for further action if needed. And he was absolutely needed.

In August 1777, the British Army was moving down from Canada, taking Fort Ticonderoga and working towards Albany. The goal was to meet with the British forces coming up the Hudson River from the New York and cut off New England from the rest of the colonies. This would effectively end the war as the British would control the flow of people and supplies. British General John Burgoyne led an expedition to Bennington to raid supplies stored there. That’s where he ran into the combined forces of Vermont and New Hampshire, led by 49 year-old John Stark.

As Stark rallied his troops to attack the British, he shouted the second-most famous sentence he ever produced; “There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!” The first half of that statement is contested. What seems to have consensus is the “Molly Stark sleeps a widow” part. Hell of a rallying cry for sure. During the battle, Stark showed his strategic mind once again by flanking the combined forces of the British, Loyalists, Indians and Canadians in a double envelopment, creating panic in the ranks of the enemy. Many of them fled, leaving the British to face a full frontal assault from the majority of Stark’s New Hampshire men, which routed the British and set the stage for victory at Saratoga.

John Stark, like General Sherman after the Civil War, chose to retire from the spotlight and move back to his farm in New Hampshire. He lived out his life on his farm in Derryfield (now Manchester). At the age of 82 he declined an invitation to participate in events commemorating the Battle of Bennington as his health was declining. Instead, he sent a note with a toast to his old soldiers participating in the events. It contains his most famous words, familiar to most everyone even if they don’t recall the source; “Live free or die: Death is not the worst of evils.”