We stayed on St. David’s Island this week while we were in Bermuda. It wasn’t a conscious choice to stay there, but I’m pleased we did, for otherwise I don’t believe we would have gotten there on this particular trip. When I speak of conscious choices, I want to acknowledge that unconsciously I knew the connection between New England and Bermuda. In particular, between Rhode Island and St. David’s Island. Not simply the famous sailing race, but the historic slave trade. Bermuda was the destination for many of those “problematic” Native Americans who were being crowded out by waves of settlers changing the landscape of North America.

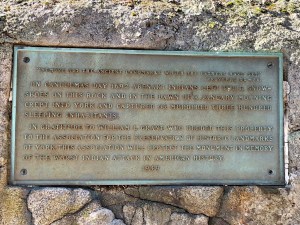

One generation after the Pilgrims were saved in their first brutal winter in Plymouth, their saviors’ offspring were fighting for survival in what became known as King Philip’s War (1675-1676). King Philip was the English name for Metacomet, Chief of the Pokanoket, who’s seat was in Mount Hope, Rhode Island. The direct descendants of the Pokanoket are the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe. When Metacomet was eventually tracked down and killed, ending the war, his wife Wootonekanuske and their son were sold into slavery in Bermuda, meeting the fate of many other Native Americans. Mother and son were separated on the island and lived out their lives as slaves. The son was said to have been on St. David’s Island.

What seems completely separate is often connected in ways we don’t always understand. Our histories all blend together at some point, sometimes generations later. The story of humanity is tumultuous, tragic and beautiful all intertwined as a tapestry. One thread leads to the next, and we are one. We are forever learning, forgetting and relearning those connections. In a place called St. David’s Island, or in Bristol, Rhode Island, we find those threads and are reminded that our stories will forever be one and the same, even as our outcomes diverge.