“Certainly there is within each of us a self that is neither a child, nor a servant of the hours. It is a third self, occasional in some of us, tyrant in others. This self is out of love with the ordinary; it is out of love with time. It has a hunger for eternity.” — Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays

We wrestle with the ordinary, biding our time for moments of blissful vibrancy. In a creative lifespan that is so very brief, what is it about time that has such a hold on us? This third self Oliver describes, and which many of us know to be true, must feel the urgency of the moment and scramble where it might lead us. Doesn’t our creative work lead us out of our fragile self into something more eternal? We don’t have to reach mastery to feel this, but we do need to be present with our work and giving the best of ourselves in that moment.

“The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.” — Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays

We must jealously protect our time, that we may do something with it. To be productive with it, whatever that means to each of us. We only have so much life force in the well, so make it matter.

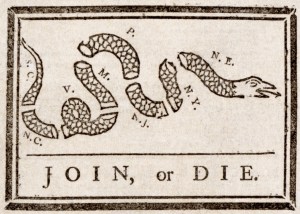

“Dost thou love life? Then do not squander Time; for that’s the Stuff Life is made of.”— Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Lately I’ve been accused of giving my time to others who desperately need it. We all need it, of course, for time is all we have. We must always ask ourselves what we give up for the life we say yes to. Would this time be better served in service to our art, or to our loved ones? To our careers or ourselves? These are decisions with consequences. For what will become of us next? Giving isn’t squandering, not when we give it freely. Yet we must give time to the other stuff that calls for our attention.

There are reasons I write early in the morning. It’s mostly because it’s the only time I can claim as my own. Let them all sleep, as lovely and essential they may be, and leave me to my work. The rest of the day will be yours. Just as soon as I click publish once again. Is this enough to satiate the muse? Let’s hope not. But it’s enough for now.