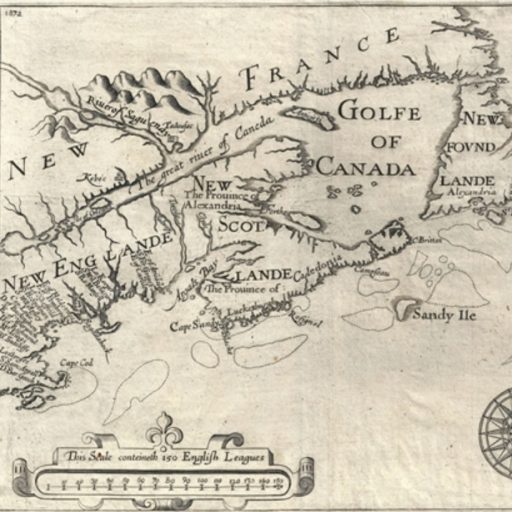

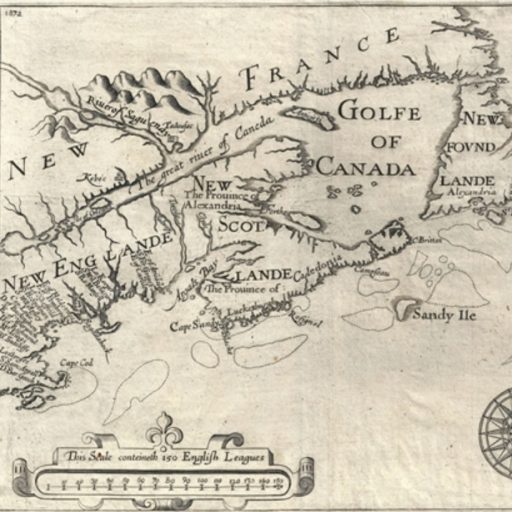

The Gulf of Maine is a corner of the Atlantic Ocean embraced by Cape Cod to the South and Nova Scotia to the Northeast. The longest stretch of land in between is part of Maine, which gives the gulf her name. If you look at Alexander’s map, which this blog is named for, the body of water is just below the land described as “New Englande” and “New Scot Lande”. A land mass that I’ve grown to love, that I declared I’d explore more, and that I need to return to in earnest once this pandemic is behind us.

Yesterday we had the opportunity to sail on Fayaway with friends. It was an out-and-back sail with one tack. We left the Merrimack River where they moor Fayaway when they aren’t exploring the world and sailed generally on a compass heading of 90 degrees, which took us roughly along the coast of Maine just out of sight of land. Sail for 18 miles out one way, tack and return 18 miles the other way. Not a lot of tactical sailing required, which was perfect for a day of conversation and contemplation on the water. We had a secondary objective of seeing whales and maybe that evasive Comet Neowise, but each proved elusive on this trip. A sunfish made an appearance, which was akin to an understudy playing the role when you came to see the star: Wasn’t what you came for, but turned out to be entertaining just the same.

When we got out of the lee shore of Cape Ann the wave action picked up, with 3 to 6 foot swells that lifted Fayaway and reminded us we were well out at sea. But Fayaway handles wave action well, and with her sails reefed in the 28 – 30 knots of sustained wind were comfortable for the duration. Which invited conversation about travel and plans for the future and the kind of catching up you do when it’s just you and others and the wind and splash of waves for hours.

I’ve learned that I’m a bit rusty with ancillary sailing terminology that goes deeper than the basic rigging, and assisted where appropriate while staying out of the way the rest of the time. When you see a couple who have sailed together for a year covering thousands of miles you’re witnessing a well-choreographed dance. I’m not the sharpest knife in the drawer but I know enough not to be the clumsy fop who thumps onto stage mid-act. Instead be the quiet stagehand who puts away the props when the performers are done. I was grateful for a patient crew who recognized the rustiness in this sailor.

There are a few highlights when you sail up the coast from the Merrimack. You begin with the chaos of the Merrimack River with powerboats and jet-skis racing to win perceived races to get “there”. It reminded me of aggressive drivers on the highway shifting two lanes and back to get one car ahead. Its the antithesis of the sailing we were doing, and I greatly prefer being out of that race. Once you clear the Mouth of the Merrimack, sails are up and you set course for nowhere in particular. The lines of umbrella stands on Salisbury Beach and elbow-to-elbow fishermen and women on charter boats indicate that social distancing is a guideline many choose to ignore. I’m sure plenty were doing their best to be socially responsible, while others proved more reckless. I considered the similarities between drivers on the highway, power-boaters racing each other in a narrow channel to get to the fish first and close-talking beach umbrella bunnies in a pandemic for a moment, and released the thought onto the breeze. We all live our lives in our own way in America, if not always responsibly. I was observing from the vantage point of a sailboat in close proximity with another couple, but with the mutual assurance that each couple was taking appropriate measures to avoid COVID-19 exposure. Maybe those beach throngs were doing the same thing. I hope so.

Soon Fayaway moves beyond umbrellas, beyond the sight of land, beyond the hum of motorboats, and we’re in our own world. For much of the duration of our trip out and back we were completely alone other than a couple of commercial fishing vessels busily working the waters of the gulf. Time on the water gives you time to ponder and think, and, if you let it, to look through the swirling waves deep into yourself. And Sunday became another micro adventure for the books. Leaving terra firma for the sea and exploring a relatively small segment of the Gulf of Maine. It served as a reminder that I have far to go, but where I am isn’t all that bad either.