The walk up Pleasant Street gives you a sense of what the British were up against, and why the American militia chose this spot. Beginning at The Warren Tavern, the climb is gradual at first, but very steep as you approach the crest. Waking up to a locked and loaded enemy staring down that hill would have been unacceptable, and action would be required. Just the sight of the British regulars lined up and marching towards you must have been terrifying, and the British knew that and counted on the effect it would have. But on this day terror wouldn’t budge the bold easily.

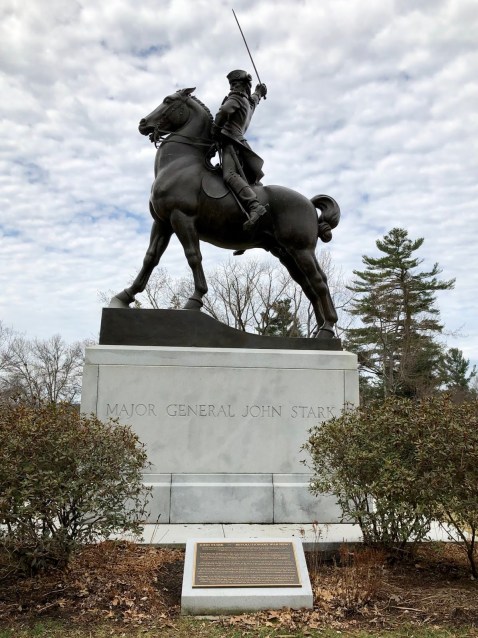

Events of that day are well-documented. Heroic figures rose up, died or survived to fight another day. William Prescott commanded the Americans, uttering some of the most famous words of the war (in a war full of famous words) when he shouted to his nervous militia “Do not fire until you see the whites of their eyes!” to conserve ammunition. Israel Putnam and John Stark were heroes that day as well, using their experience in the French and Indian War to offer critical tactical insight. The British side features famous names as well; Thomas Gage, William Howe, Henry Clinton, James Abercrombie and John Pitcairne. For the latter two Bunker Hill would be their last battle.

The Bunker Hill Monument stands on Breed’s Hill, which is where the bulk of the fighting took place on June 17, 1775. I’ve driven by the monument thousands of times, but only remember climbing up the stairs inside once. Not in the cards on the day I visited either, as my walk up from the tavern around the perimeter and a bit of time to re-marinate myself in my local history chewed up all of the allocated time. But I was pleased with the site, which offers appropriate reflection.

I’d started by walk up the hill at The Warren Tavern, founded five years after the battle and named for Joseph Warren, the 2nd President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, who would become a martyr that day. Warren refused the safety his position offered him and choosing instead to be where the fighting would be worst. He died from a musket ball to the head, and then had his body brutalized by the British, whose heavy losses taking the hill likely inspired vengeance. Warren’s close friend Paul Revere helped exhume his body for burial elsewhere, a sign of the great respect Warren had earned in his life.

That the bulk of the battle happened on Breed’s Hill is mostly known, but people still think the monument is on Bunker Hill. Sometimes the details get mixed up in the story telling. I love a good story and there were many on that hill on June 15, 1775. I’d say I’m better than many in knowing those who came before, but as with everything you learn as much about what you don’t know, and I appreciate a good refresher course. I’ll dance with the ghosts longer next time. There’s so much more to learn from them.