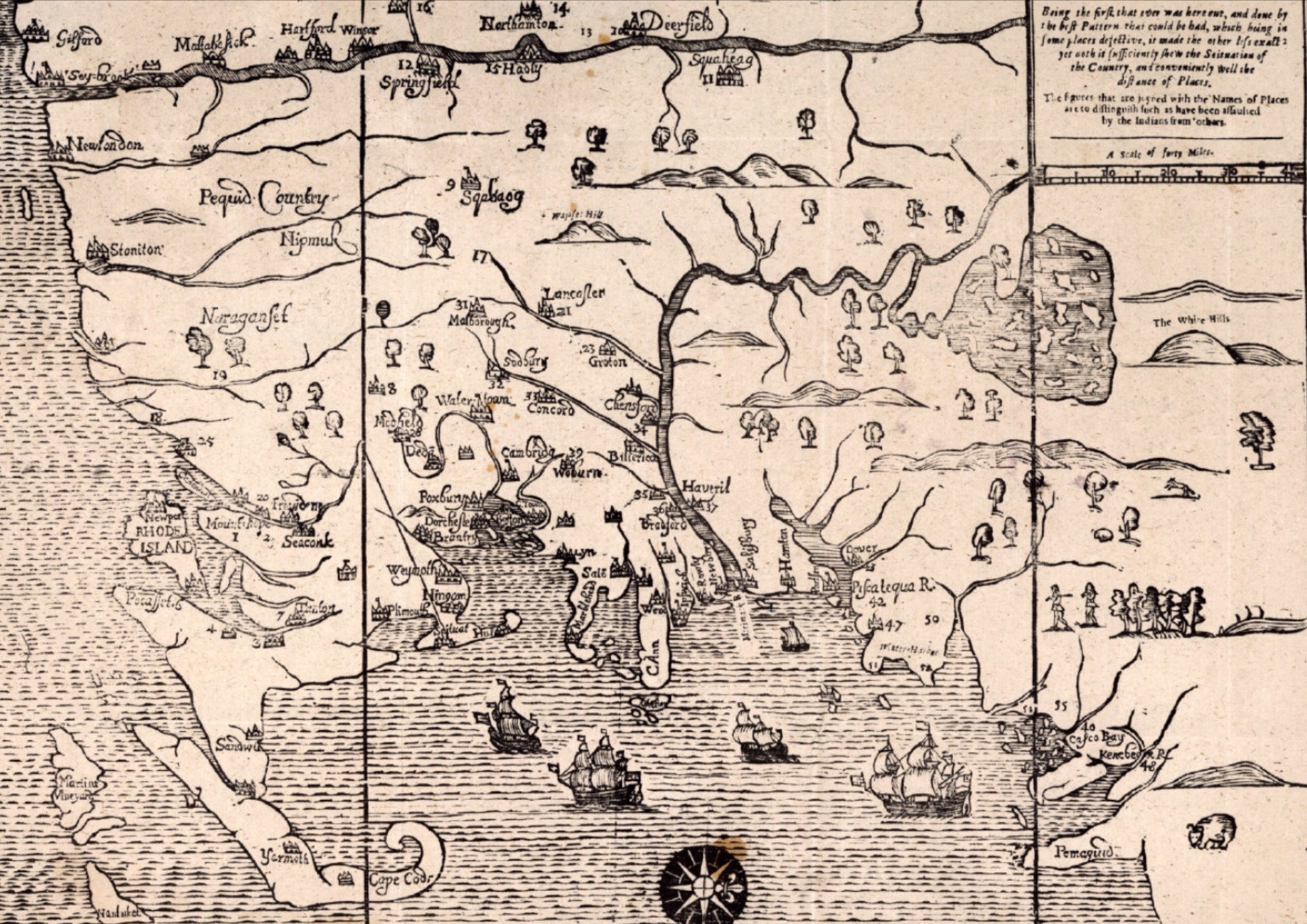

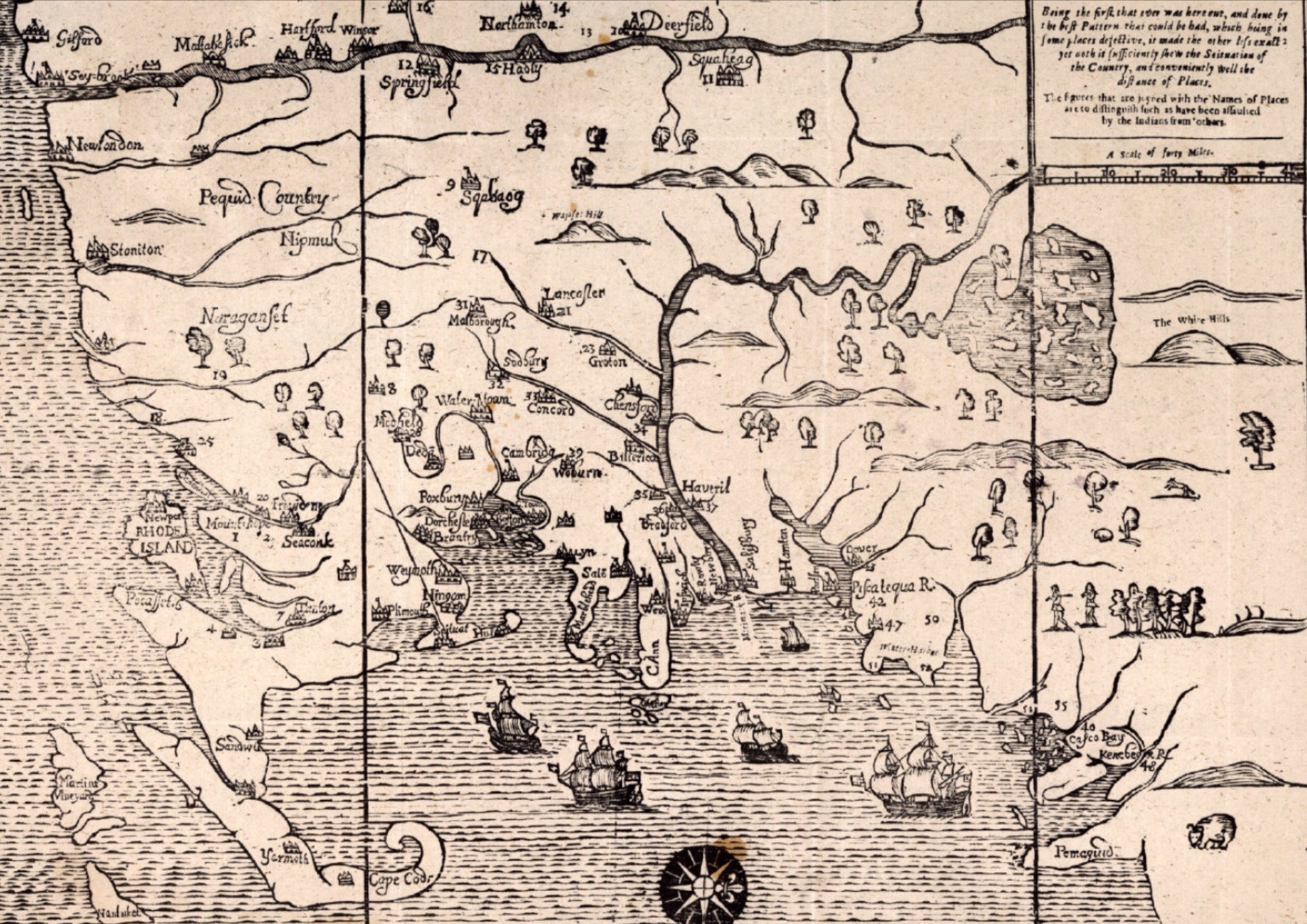

Yesterday I dove deep into the Cape Cod section of John Seller’s Mapp of New England. Today I’m looking at another fascinating section – the border between “civilization” and the “wilderness’. I’ve written before about place names like World’s End Pond in Salem, New Hampshire. Nothing hammers that home like seeing a map from 1675 showing the Merrimack River towns of Haverhill (“Haveril“), Billerica and Chelmsford (“Chensford“) Massachusetts as the frontier towns they were at the time. North of the Merrimack River is wilderness in this map, South are the growing settlements of Massachusetts. The river serves a critical role for settlers and Native Americans alike as both transportation and a border. Settlements at this time were largely along the rivers and their tributaries, the Concord and Nashua Rivers.

That bend in the Merrimack River northward was a critical point in the understanding of this land. Isolated outposts like Billerica, Groton and Lancaster represented the outer reaches of people like us. The map shows Lake Winnipesaukee and its many islands, so there was clearly knowledge in 1675 of what lay beyond, but it remained for all intents and purposes a vast, dangerous wilderness for another century until the fortunes of war, attrition in the Native American population and the shear mass of settlers from Europe turned the tide.

It’s no surprise that the most notable Indian raids of the day were happening along the frontier. York, Haverhill, Andover, Billerica, Chelmsford, and Groton all suffered Indian raids during the series of wars between the French and British. Further west Brookfield and Deerfield had similar raids. These frontier towns were dangerous places, and the settlers there would rarely venture out to tend their fields unarmed. Towns like Haverhill were building fortifications and the brick 1697 Dustin Garrison for a measure of protection in the years spanning King Williams War and Queen Anne’s War.

There were a series of conflicts between the English settlers and the Native American population that impacted northern New England. In all cases the underlying conflict between the expansion of English settlements and the encroachment on the Native American population was a key factor. French influence on the Native American tribes also contributed significantly in many of the raids in Merrimack River Valley from 1689 to 1713 as raiders were offered rewards for scalps and prisoners. Living in this area for most of my life I see many reminders of that time in our history, and I always glance over at World’s End Pond and the Duston Garrison whenever I pass either. Duston’s wife Hannah was famously kidnapped during King William’s War, her baby and many neighbors killed, marched through the town I live in by Abenaki warriors, and later escaped back down the Merrimack River on one of those raids.

Wars Impacting Northern New England in the Early Colonial Period:

- King Philip’s War 1675-1678 (Northeast Coast Campaign vs. Wabanaki Confederacy)

- King William’s War 1689 – 1697 (French and Wabanaki Confederacy)

- Queen Anne’s War 1702–1713 (French and Wabanaki Confederacy)

- Dummer’s War 1722-1726 (Wabanaki Confederacy)

- French and Indian War 1754 – 1763 (French and Mohican, Abenaki, Iroquois and other tribal alliances)

So Seller’s Mapp of New England was a living, breathing document that was strategically important to the British and by extension the English settlers living in New England. If matters were largely settled with the Native American population in the Southern New England areas by 1675, they were anything but settled in Northern New England. Northern Massachusetts, including what is now coastal Maine and New Hampshire were the literally on edge, looking north and west for raiders. That they would ultimately overpower the Native American population and New France settlements was not a foregone conclusion at the time. Another reason it completely fascinates me.