I wasn’t planning on another detour on this trip, but saw the sign, calculated the total time the detour would take and made the decision to stop by the battlefield. I was deeply impressed with the quiet dignity of the site, and reflected on the violence that took place in the ravine I walked down into. The battlefield is nothing but tranquil today, save for the landscaper mowing the fields. But at 10 AM on August 6, 1777 this valley erupted in thunderous clouds of gunfire and screams the hidden Loyalists and Iroquois aligned with the British ambushed a column of American patriots and Oneida Indians allied with them. That this battle pitted neighbor against neighbor, Iroquois tribe against Iroquois tribe makes the results all the more devastating.

“We met the enemy at the place near a small creek. They had 3 cannons and we none. We had tomahawks and a few guns, but agreed to fight with tomahawks and scalping knives. During the fight, we waited for them to fire their guns and then we attacked them. It felt like no more than killing a Beast. We killed most of the men in the American’s army. Only a few escaped from us. We fought so close against one another that we could kill or another with a musket bayonet…. It was here that I saw the most dead bodies than I have ever seen. The blood shed made a stream running down on the sloping ground.” – Blacksnake, Seneca War Chief

When I decided to divert from I-90 to check out the battlefield, I had no idea what to expect. I’d seen pictures of the monument, but there’s an emotional weight in walking in the footsteps of those who perished here down into that ravine, across the creek and up the other side. The land looks remarkably similar to what it looked like then. Perhaps more fields have replaced the deep forest of the day, but this area remains largely undeveloped, and will remain so as the Oriskany Battlefield State Historic Site.

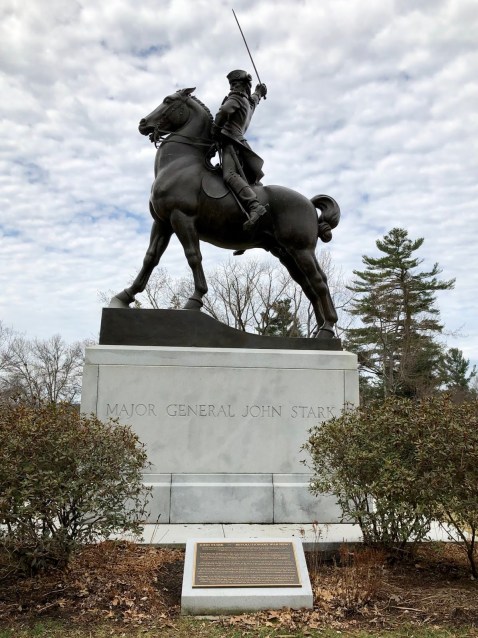

So I pulled into the driveway leading to the monument and drove down to the parking area. The 85 foot tall oblisk built in 1883 dominates the landscape in front of you. But I’d noticed another monument and some signs marking historically relevant locations on the battlefield off to the right as I drove in, and decided to walk over to check those out first. This is the best approximation of where the ambush took place, and looking around it seemed as appropriate a spot as any. I walked up to the monument honoring General Nicholas Herkimer, wounded in the initial ambush, who famously directed patriot forces into defensive positions from behind an ash tree at or near this location. The Iroquois warriors would wait for a soldier to fire their one shot then rush at them with tomahawks and knives. This was up close, brutal fighting that decimated the American forces. Herkimer directed his men to pair up, with one firing while the other reloaded, to counter this rush. Herkimer was shot in the leg, and died when the amputation to save him didn’t go as planned. I wonder sometimes if Benedict Arnold, shot in the leg later in the same year, refused to have his leg amputated after seeing what happened to Herkimer?

Of the almost 800 American and Oneida ambushes, almost half were killed, and overall casualties were over 500. For the patriotic farmers who rallied to save their brothers-in-arms under siege at Fort Stanwix, the ambush quickly ended their dreams and destroyed the lives of their families back home. By all accounts these were tough losses for any army, but for Tryon County, it was a devastating loss of fathers, brothers and sons that brought the county to its knees.

Ultimately the relief column suffered far more casualties than the defenders at Fort Stanwix, who were saved when Benedict Arnold orchestrated a con to make the British and Iroquois think he was much closer to engaging with them, and with many more troops than he actually had. But that’s a story for another day. The Loyalists who survived would eventually flee to Canada or other British territories as reprisals reached their homes as momentum swung away from the British. While the battle at Oriskany was a huge setback in momentum, it was another domino in the string of events that led to the defeat of General Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga.

On this rainy June afternoon, I had the place largely to myself. There were about a dozen New York State Troopers visiting, a couple huddled under an umbrella, a man walking two Labrador retrievers, and… me. The experience reminded me of my trip to Hubbardton a couple of months ago, the quiet solitude and signs describing the lay of the land on the day of the battle were similar. But Oriskany felt different, because what happened here was different. Hubbardton was a retreating rear guard being caught by a faster moving British force. Oriskany was neighbors ambushing neighbors. Iroquois tribe against Iroquois tribe. A mass casualty event that shook a region. The Revolutionary War was far more complicated than Americans overthrowing a tyrannical oppressor. It was a messy divorce that forced each individual to decide which parent they were going to remain with, and which one they would betray in the most violent ways.

Visiting the Oriskany battle site is easy. Roughly ten minutes off I-90, it offers a quick respite from travel, and perspective on the sacrifices others made to give us the freedom to do so. On the day I visited, as with other battlefields related to the Saratoga campaign, a quiet stillness prevailed. There’s a small building set down behind the monument where you can learn more about the site and events that day, and (please) leave a donation to help support the maintenance of this sacred ground. The obelisk is showing signs of wear and needs renovation, but remains a striking tribute to those who fell here.