I re-read The Dip, by Seth Godin. I’m definitely in a Dip at my present job, and I have several opportunities to change being dangled in front of me. So I figured I’d re-read this quick book to add some clarity to my thinking. Here are my highlighted notes from my second reading of this book. The question is, does this Dip matter? Will slogging through it offer enough reward in the end, or am I wasting time in a Cul-de-Sac/dead end? The question goes beyond a job of course. The Dip can be applied to any decision.

“Winners quit all the time. They just quit the right stuff at the right time.”

“Quit the wrong stuff.”

“Just about everything you learned in school about life is wrong, but the wrongest thing might very well be this: Being well rounded is the secret to success.”

“In a free market, we reward the exceptional.”

“Strategic quitting is the secret of successful organizations. Reactive quitting and serial quitting are the bane of those that strive )and fail) to get what they want. And most people do just that. They quit when it’s painful and stick when they can’t be bothered to quit.”

“The Dip is the long slog between starting and mastery.”

Scarcity, as we’ve seen, is the secret to value. If there’s wasn’t a Dip, there’d be no scarcity.”

“Successful people don’t just ride out the Dip. They don’t just buckle down and survive it. No, they lean into the Dip. They push harder, changing the rules as they go. Just because you know you’re in the Dip doesn’t mean that you have to live happily with it. Dips don’t last quite as long when you whittle at them.”

“The Dip creates scarcity; scarcity creates value.”

“The people who set out to make it through the Dip – the people who invest the time and the energy and the effort to power through the Dip – those are the ones who become the best in the world.”

“In a competitive world, adversity is your ally. The harder it gets, the better the chance you have of insulating yourself from the competition. If that adversity also causes you to quit, though, it’s all for nothing.”

“And yet, the real success goes to those who obsess.”

“Before you enter a new market, consider what would happen if you managed to get through the Dip and win the market you’re already in.”

“Not only do you need to find a Dip that you can conquer but you also need to quit all the Cul-de-Sacs that you’re currently idling your way through. You must quit the projects and investments and endeavors that don’t offer you the same opportunity. It’s difficult, but it’s vitally important.”

“Most of the time, if you fail to become the best in the world, it’s either because you planned wrong or because you gave up before you reached your goal.”

“The next time you catch yourself being average when you feel like quitting, realize that you have only two good choices: Quit or be exceptional. Average is for losers.”

“Selling is about a transference of emotion, not a presentation of facts.”

“If you’re not able to get through the Dip in an exceptional way, you must quit. And quit right now.”

“The opposite of quitting is rededication. The opposite of quitting is an invigorated new strategy designed to break the problem apart.”

“Short-term pain has more impact on most people than long-term benefits do, which is why it’s so important for you to amplify the long-term benefits of not quitting. You need to remind youself of life at the other end of the Dip because it’s easier to overcome the pain of yet another unsuccessful cold call if the reality of a successful sales career is more concrete.”

“Persistent people are able to visualize the idea of light at the end of the tunnel when others can’t see it. At the same time, the smartest people are realistic about not imagining light where there isn’t any.”

You and your organization have the power to change everything. To create remarkable products and services. To over deliver. To be the best in the world. How dare you squander that resource by spreading it too thin.”

“If it’s not going to put a dent in the world, quit. Right now. Quit and use that void to find the energy to assault the Dip that matters.”

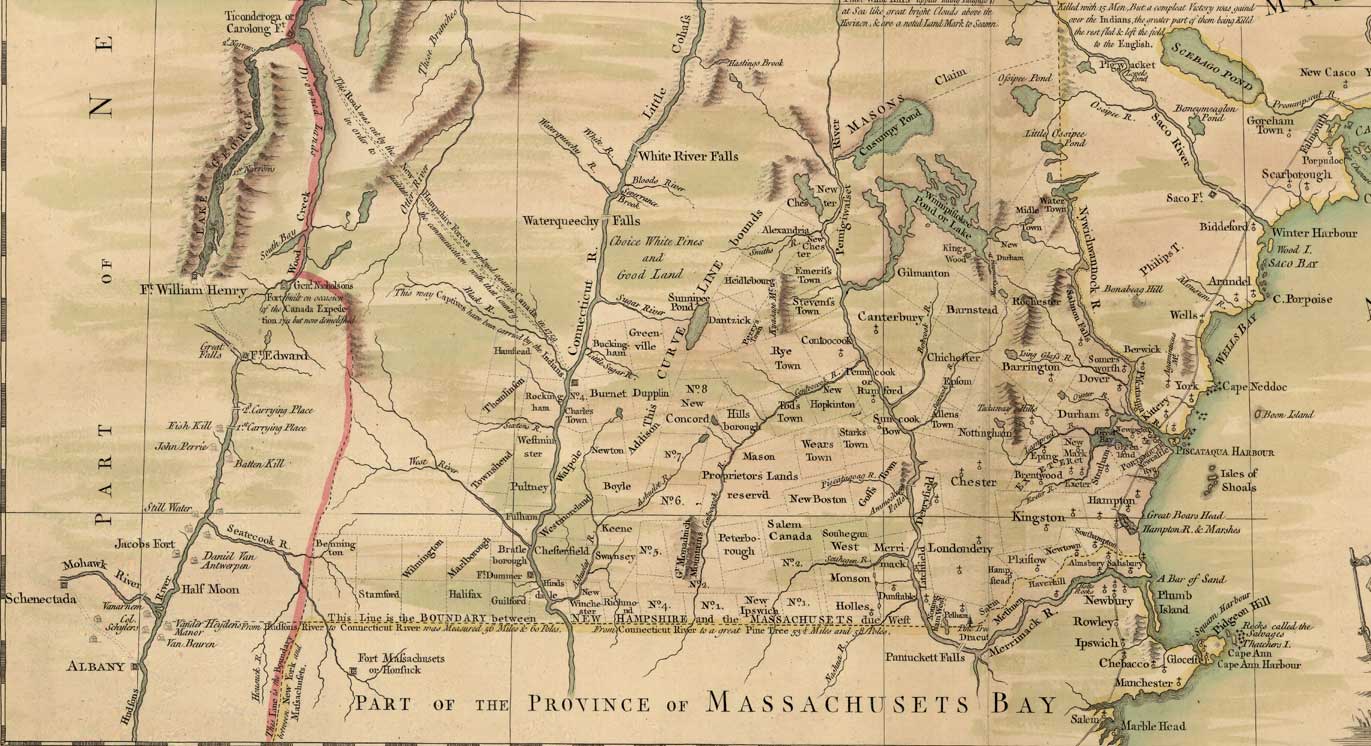

Joseph Blanchard was born in the Nashua area and served as a Colonel during the French and Indian War. He teamed with Samuel Langdon to create this map, which was published after Blanchard’s death. It’s an amazing time capsule that highlights some contentious early days in our colonial history. For me, the part of the map I love the most is in the present-day Plainfield/Montcalm area where the map designers noted “choice white pines and good land”. A name like Montcalm jumps out if you’re talking about the French & Indian War, but apparently it’s not what the selectmen in that town were striving for when they named it.

Joseph Blanchard was born in the Nashua area and served as a Colonel during the French and Indian War. He teamed with Samuel Langdon to create this map, which was published after Blanchard’s death. It’s an amazing time capsule that highlights some contentious early days in our colonial history. For me, the part of the map I love the most is in the present-day Plainfield/Montcalm area where the map designers noted “choice white pines and good land”. A name like Montcalm jumps out if you’re talking about the French & Indian War, but apparently it’s not what the selectmen in that town were striving for when they named it.