During the French and Indian War the pristine Lake George saw some horrific battles for control of the lake. The British and French continued attempts to push each other out of the region with force. The Battle of Lake George in 1755, the siege on Fort William Henry in 1757, the Battle on Snowshoes in 1758 and countless skirmishes in between let to high body counts on both sides. One relatively small battle in 1755 illustrates just how bloody the fighting was.

The New Hampshire Provincial Regiment, consisting of a company of men led by Colonel Nathaniel Folsom (including Robert Rogers in his first battle) plus another 40 New York Provincials under Capt. McGennis came across the baggage and ammunition that the French had left protected with a guard. They quickly overwhelmed the guard and waited for the larger force of French Canadians and their Indian allies to return. Late in the afternoon a combined force of roughly 300 returned to the camp and walked into a field of fire from the New Hampshire and New York milita. In this battle over two hundred men were killed, and subsequently rolled into the pond, which turned red as the blood of the French, Canadians, Native Americans, and colonial militia mixed together in the water. Enemies returning to the earth together.

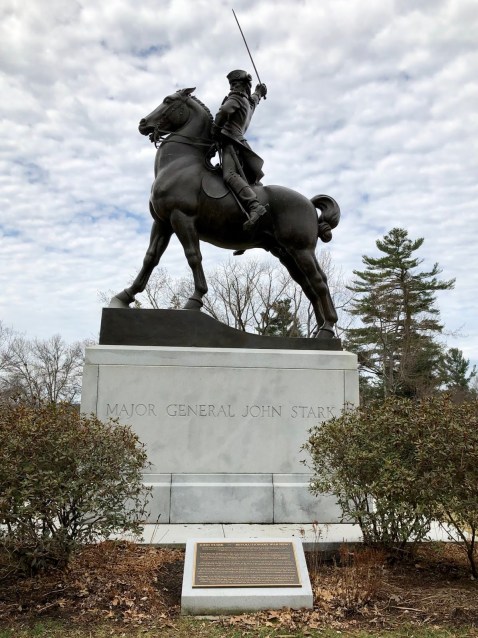

McGennis didn’t survive the battle. Folsom did, and would go on to participate in other battles of the French and Indian War, and then took up arms in the Revolutionary War. Folsom and John Stark were both leaders in the New Hampshire Militia. Folsom was a delegate representing New Hampshire in the the Provincial Congress and ultimately the Continental Congress. By all accounts I’ve read he led a life of service to New Hampshire and the country.

I visited the Winter Street Cemetery to visit Major General Nathaniel Folsom. I wasn’t sure where his gravestone was when I got there, but looking around I noticed that there weren’t that many that had American flags posted next to them so I used that as my starting point. I walked around that cemetery for 40 minutes reading each gravestone. Most of the Revolutionary War veterans had a similar shape and size, with the unique badge carved in the front. And yet I couldn’t find Folsom’s gravestone. Folsom was a hero of two wars for the American Colonies, he must have a flag, right? No flag. Perhaps it blew over in the wind, or someone took it, or someone forgot to place one next to his gravestone to honor him. Who knows?

My time was limited, and I still hadn’t found Nathaniel Folsom. But I did find the graves of his fellow Revolutionary War veterans, and read the family names of the people who were his neighbors and friends. And finally it was time to go, and as I stood near the gate I thought I’d just walk down the middle one last time and try an area I hadn’t recalled walking past in my search… and there he was. His was quite literally one of the very last gravestones I came across. It’s almost like he wanted me to pay my respects to the rest of the people in the cemetery before coming to see him.

Like other roadside monuments, the small memorial on Route 9 in Lake George, New York, crowded by motels, auto parts stores and a sushi restaurant, called out to me as I drove by. It led me to read more about Nathaniel Folsom and eventually to my visit to his home town and final resting place. For all that he did for his state and his country, his grave is modest – no different than those of other soldiers from the Revolutionary War buried nearby. If these two modest monuments bookend his life, they served their purpose by helping me get acquainted with this gentleman from Exeter.